SHM Submits Comments on MACRA

June 26, 2016

SHM's Policy Efforts

SHM supports legislation that affects hospital medicine and general healthcare, advocating for hospitalists and the patients they serve.

Download Letter

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

Department of Health and Human Services

Attention: CMS-5517-P

P.O. Box 8013

Baltimore, MD 21244-8013

Dear Acting Administrator Slavitt:

The Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) is pleased to offer comments on the proposed rule entitled Medicare Program; Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) and Alternative Payment Model (APM) Incentive under the Physician Fee Schedule, and Criteria for Physician-Focused Payment Models (CMS-5517-P). The implementation of the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA) will have far-reaching effects on the practice of medicine by incrementally moving physician payments away from traditional fee-for-service. In this proposed rule, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) details regulations for implementing two pathways for physician payment: the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) and alternative payment models (APMs).

Hospitalists are front-line providers in America’s hospitals, providing care for millions of hospitalized patients each year, many of whom are Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries. In their role, hospitalists manage the inpatient clinical care of their patients, while working to enhance the performance of hospitals and health systems. The position of hospitalists within the healthcare system affords a distinctive role in facilitating care both at the individual, physician-level as well as at the systems or hospital level. This includes participation and performance assessment in programs around value-based purchasing and quality improvement. These experiences inform our comments on the proposed rules for the MIPS and APMs.

SHM’s approach to comments on MACRA is defined by one characteristic: choice. In our comments, we aim to ensure that hospitalists and providers in general have a realistic option to choose to participate in either the MIPS or APMs, rather than be forced into one pathway over the other. We believe this is consistent with the intent behind the law, and such flexibility would encourage providers to select the pathway that best fits and represents their practice of medicine.

II. E. MIPS Program Details

II.E.2. MIPS Eligible Clinician Identifier

For the purposes of reporting in the MIPS, CMS proposes to identify individual Eligible Clinicians (ECs) by a combination of the Taxpayer Identification Number and National Provider Identifier (TIN-NPI). Groups would be identified solely by their TIN. APM participants would be identified by a combination of the APM Identifier, APM Entity Identifier, TIN(s) and NPI. CMS also proposes that the same identifier must be used for reporting throughout all four MIPS categories; that is, if a group decides to report as a group, they must do so for all four categories.

SHM supports these proposals. However, as CMS moves to operationalize the MIPS, we remind CMS that past experience using the TINs as identifiers in pay-for-performance programs has yielded mixed results. Hospitalist groups have reported serious issues with the accuracy of the TINs, which diminishes trust in performance rates and other program metrics. For example, if providers who have never worked within a group were included in TINs, it could negatively impact groups’ performance on the measures and within the broader pay for performance programs. SHM strongly asserts that NPIs associated with a given TIN must be accurately matched in real time or as close to real time as possible. To ensure this, CMS must establish clear and efficient mechanisms for groups to resolve inconsistencies or problems with TINs and safeguard that administrative processes and appeals are streamlined in ways that recognize the fluid nature of medical practices and provider mobility.

II.E.4. MIPS Performance Period

CMS proposes to use the full calendar year, two-years prior to the payment adjustment year as the performance period for all four MIPS categories. For individual ECs and group practices that have less than a full year’s data to report, such as when providers switch practices, those ECs and group practices would be required to report on as much data from the performance year as possible and would be subject to MIPS payments as long as they meet the low-volume threshold and the minimum sample size for each measure and activity.

SHM notes that the timing between the finalizing of these policies and the start of the performance year is incredibly short, which may make it difficult for providers to digest and implement practice changes in order to meet the new requirements. We advise CMS to take this into account as they finalize policies in the first year and, if possible, either consider the first performance year to be a trial run with no penalties attached or delay implementation to give more time for provider education.

SHM supports the proposed expectations for reporting when providers change groups or have some other break in their practice. SHM has previously voiced concerns about providers who change groups or practice as locum tenens physicians and the negative impact they may have on groups’ performance in PQRS and the value-based payment modifier. We believe that CMS’ proposals may help mitigate these concerns and enable groups to have a consistent reporting expectation for all of their providers under the MIPS.

II.E.5. MIPS Category Measures and Activities

II.E.5.a.2. Performance Category Measures and Reporting: Submission Mechanisms

SHM greatly appreciates that CMS proposed to continue to allow claims-based reporting for the Quality Performance Category. Many hospitalists report on quality measures by either the claims or registry methodologies. Billing data is the most readily, and frequently only, available information for hospitalists. Maintaining claims-based reporting enables a continued reporting pathway for a significant number of hospitalists.

II.E.5.b Quality Performance Category

II.E.5.b.3.a.i. Submission Criteria for Quality Measures Excluding Web Interface and CAHPS for MIPS

CMS proposes to reduce the number of required quality measures from nine (9) to six (6) and eliminate the requirement for measures within defined National Quality Strategy Domains. Of those six measures, CMS proposes to require one cross-cutting measure and at least one outcome measure. In parallel, CMS also created a number of specialty measure sets that enable providers to look at subsets of measures tailored to their specialty and, if there are fewer than six measures, report on the most relevant measures without penalty.

SHM supports this reduction in reporting requirements for the quality measure category, but cautions that a requirement of six measures may still be out of reach for many providers. The requirement of 9 measures across three National Strategy Domains under PQRS was difficult to achieve for hospitalists and confounded good-faith efforts to report on the available and applicable quality measures. We note that even with the lower number of required measures, many hospitalists will still struggle to meet the requirements for this category. For claims based reporting, hospitalists only have four, possibly five, measures to report.

CMS proposes that “If fewer than six measures apply to the individual MIPS eligible clinician or group, then we propose the MIPS eligible clinician or group would be required to report on each measure that is applicable.” This would seem to suggest that providers can report on fewer than six measures without immediate penalty (i.e., a zero on each unreported measure) in the category. However, the section on scoring in the Quality Performance Category (section II.E.6.a.2) does not appear to make complementary proposals that reference this outcome. SHM requests significant clarification on this language in the proposed rule and recommends that CMS maintain policies that do not penalize providers who cannot report on six measures due to a lack of applicable measures or availability of measures.

SHM is disappointed that CMS did not include a specialty measure set for hospitalists. Over the past two years, SHM and hospitalist groups worked closely with CMS officials to develop a specialty measure set for hospitalists to report under PQRS. In addition, through our work with CMS on this set, we helped identify issues with the Measures Applicability Validation (MAV) process and advocated for many of the changes reflected in this rule. As proposed, the MIPS specialty measure sets are a sort of front-loaded MAV process, facilitating measure reporting decision-making and boosting provider confidence in their submissions. We strongly urge CMS to adopt a specialty measure set for hospitalists for the following reasons:

- Hospital Medicine is a Specialty. On February 23, 2016, CMS issued a letter approving a Medicare physician specialty billing code for hospitalists. Among a variety of reasons, SHM applied for a specialty billing code for hospitalists to enable fair identification and comparison of hospitalists within Medicare pay-for-performance programs. As CMS noted in their approval letter, it will take up to a year for the system changes and scheduling of implementation of the billing code, meaning this specialty identifier will be live during the 2017 performance year.

- A Hospitalist Specialty Measure Set Already Exists. For the last two PQRS reporting years, CMS has posted a hospitalist specialty measure set at https://www.cms.gov/medicare/quality-initiatives-patient-assessment-instruments/pqrs/measurescodes.html. This measure set reflects significant work and agreement between SHM, hospitalist groups, and CMS to identify measures within the available measures list that are relevant and reportable by hospitalists. As part of this agreement, CMS extended an offer to protect hospitalists from the MAV process that was associating inappropriate outpatient measures for reporting and therefore causing hospitalists to fail. This is similar to the intent behind the MIPS specialty measure sets.

- The MIPS Measure List Contains Few Inpatient-Specified Measures. As CMS indicated in the proposed rules, one of the common complaints about PQRS was the difficulty in determining which out of more than 300 measures a provider should report. For hospitalists, there are very few measures that are both specified for the hospital setting and relevant to the practice of general hospital medicine. By adopting a hospitalist specialty measure set, CMS would help narrow the options in both of these dimensions and avoid issues with measure applicability validation.

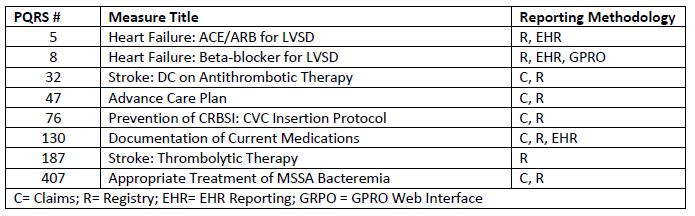

As there have not been changes to the measures available under the MIPS for hospitalists to report, we recommend CMS adopt the following measures as a hospitalist specialty measure set.

For claims based reporting, hospitalists could report on measures 32, 47, 130 and 407. Some hospitalists could report on measure 76, although this would depend on whether they are performing central line insertions. For registry reporting, hospitalists could report on 5, 8, 32, 47, 130, and 407. Some hospitalists could report on measures 76 and 187, although this depends on their individual clinical practice.

CMS proposes to develop a validation process as a check on providers who report fewer than six measures, which seems similar to the MAV process currently in existence under PQRS. SHM has consistently raised concerns about the functionality of the MAV process and how it was applied. Because of the lag between performance and payment adjustment years, providers who failed reporting due to the MAV do not have the dynamic ability to change their reported measures in the intervening year, particularly if they report through claims. SHM strongly urges CMS to work with specialty societies to develop a responsive validation process that encourages collaboration and up-front decision making tools for providers.

II.E.5.b.3.a.iii. Performance Criteria for Quality Measures for Groups Electing to Report Consumer Assessment for Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) for MIPS Survey

CMS requests comments on whether the CAHPS for MIPS survey should be required for groups of 100 or more MIPS eligible clinicians.

SHM opposes making the CAHPS for MIPS survey a requirement for large groups. As recently as the FY 2015 Physician Fee Schedule rule, CMS indicated a desire to require reporting of the CAHPS for PQRS (aka CAHPS for MIPS aka CG-CAHPS) for all providers and, particularly for larger groups. We recognize that the survey does not include hospitalists as “focal providers,” but remain concerned about mandating its use. The CAHPS for MIPS survey is a tool to measure outpatient practices and is not useful for a wide range of facility-based providers. By making the surveys a requirement for large groups, this will add significant confusion to groups as they try to determine which parts of the survey apply to them.

SHM also harbors reservations about the proliferation of patient surveys. Input from patients is an important component of assessing provider performance, however, this must be balanced by acknowledging the limitations and unintended consequences of these surveys as well as issues of survey fatigue and selection bias.

II.E.5.b.3.b Data Completeness Criteria

CMS proposes to increase the data completeness criteria for successful reporting of quality measures. For reporting via QCDR, qualified registry or EHR, ECs or groups would need to report on at least 90 percent of all patients. For reporting via Medicare Part B claims, ECs would need to report on at least 80 percent of Medicare Part B patients.

SHM does not support these increases as proposed. Under the 2017 and 2018 PQRS and VBPM policies, CMS required data completeness of 50 percent of Medicare Part B patients for both claims and registry reporting. The 50 percent threshold was a decrease from prior years, in response to concerns and issues from provider groups. We do not believe it prudent for CMS to enact a drastic increase in the reporting requirements, particularly as providers are shifting to a new pay-for-performance system. We recommend CMS maintain the 50 percent threshold in the first few years of the MIPS and, only when it is clear that 50 percent is feasible for most providers, consider phasing in increases of data completeness through rulemaking in future years.

II.E.5.b.5. Application of Additional System Measures

CMS is requesting comments on how best to operationalize using facility-level measures for the purposes of quality and resource use in the MIPS. Specifically, CMS would like more information on whether they should use facility performance, under what conditions it would be appropriate, possible

criteria for attributing facility performance, specific measures to consider, and if attribution should be automatic or voluntary.

SHM has been a consistent advocate for aligning performance agendas between hospitalists and their facilities. Hospitalists are, by the nature of their practices, team-based and systems-oriented providers; most of the proposed measures in the MIPS are not designed for the inpatient setting or for team-based care. As CMS develops options for providers to report on measures from other Medicare payment systems, we encourage CMS to keep in mind the following principles:

1. Maintain as an Option. CMS should not move towards requiring any providers to align their performance with facilities. It may be an appropriate option for some facility-based provider groups to pursue, however there are many who would not elect this option for a variety of reasons.

2. Choice in Measures. Providers should have the flexibility to choose facility measures they feel are adequately under their scope of influence and reflective of the care they are providing. This would also enable providers to choose clinical areas for focused quality improvement efforts within their facilities.

3. Flexibility in Attribution. CMS should consider a methodology that enables proportional attribution and performance assessment that is as close a proxy for a group’s practice as possible. The attribution methodology should be able to identify performance differences between hospitalist groups, or hospitalists and PCPs, practicing in the same facility. At the same time, hospitalists often practice in multiple locations, making it necessary to identify a methodology to assess performance across multiple settings.

4. Reduction of Reporting Burden. CMS should take into account how hospitalists are incentivized and/or actively working on improving facility performance on quality metrics. Hospitalists should not be required to report separately on quality measures for patients already reported through facility-level quality metrics for similar clinical concepts.

We support attributing facility performance for the purposes of the quality and resource use performance categories. As a voluntary option, this could enable greater harmony between the performance agendas of physicians and their facilities and significantly reduce reporting burdens associated with provider-level quality measurement programs.

SHM would support self-nomination at the TIN level, which allows a group to attest that it is comprised primarily of hospital-based physicians. This is consistent with our prior comments and would ensure that only those providers who wish to have this level of facility alignment would be included in the program. It would not be in the best interest of any group or specialty that does not have significant relationships and influence within the hospital to elect this option, which helps alleviate concerns about potential misuse of this option by providers.

Self-nomination could also enable providers to select which hospital(s) are appropriate for alignment. SHM believes a methodology that enables the inclusion of multiple hospitals would be necessary to implement the use of facility-level metrics. Many hospitalist groups practice in multiple locations, and as such it may not be appropriate to assign a single hospital’s performance to the TIN.

This option will allow providers, who voluntarily elect it, to align their performance on selected measures with their hospitals. This level of voluntary alignment embodies the drive towards coordinated, team-based care in the hospital. However, we stress that this should remain an option, as this level of alignment would be inappropriate for some hospitalist groups. We recognize the option to use facility metrics may not be a priority for CMS at this time, but with nearly 50,000 hospitalists being inappropriately measured and penalized, we encourage CMS to implement this option without undue delay.

SHM reviewed the available mandatory measures under the Hospital Inpatient Quality Reporting and Hospital Value-Based Purchasing programs and identified 20 existing measures (sorted into clinical clusters) that represent clinical areas of relevance to hospitalists and could be adapted for incorporation into the MIPS. These may also be measures hospitalists are already working on and potentially incentivized by their facilities and/or employer for performance. They include:

- Severe Sepsis and Sepsis Shock: Management Bundle

- HCAHPS (physician questions, possibly the 3-Item Care Transition Measure)

- Hospital-wide All-Cause Unplanned Readmission

- NHSN Measures

- CAUTI

- CLABSI

- Clostridium difficile Infection

- MRSA Bacteremia

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) Measures

- COPD 30-Day Mortality Rate

- COPD Readmission Rate

- Pneumonia Measures

- Pneumonia 30-Day Mortality Rate

- Pneumonia 30-Day Readmission Rate

- Pneumonia Payment per Episode of Care

- Heart Failure Measures

- Heart Failure 30-Day Mortality Rate

- Heart Failure 30-Day Readmission Rate

- Heart Failure Excess Days

- Payment Measure

- Medicare Spending Per Beneficiary (this has already been retooled for use in VBPM/MIPS)

- Chart-abstracted Clinical Measure

- Influenza Immunization

Other measures slated for future inclusion in the hospital-level programs that could be appropriate for this reporting option in the MIPS include:

- Cellulitis Clinical Episode-based Payment Measure

- Kidney/UTI Clinical Episode-based Payment Measure

- Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage Clinical Episode-based Payment Measure

SHM stands ready to work with CMS to explore and develop a facility-alignment option for hospitalists in the MIPS.

II.E.5.e. Resource Use Performance Category

II.E.5.e.3.a.i. Attribution

CMS proposes to expand the definition of primary care for the two-step attribution methodology in the Total per Capita Cost measure by adding transition care management codes (99495 and 99496) and chronic care management (99490). CMS also proposes to remove codes 99304-99318 with Place of Service 31 (skilled nursing facility) from the definition of primary care services.

SHM fully supports the exclusion of skilled nursing facilities from the definition of primary services, similar to policies under the Medicare Shared Savings Program. Hospitalists are increasingly providing care in SNFs, and focus on improving the transitions of care from facility to facility. Since patients in SNFs require higher intensity but time-limited care, stays in SNFs should not count towards the primary care attribution process for the Total per Capita Cost measure.

While SHM agrees that improving transitions of care is a critical aspect to improving overall patient care, we caution against adding transition care management (TCM) codes 99495 and 99496 to the definition of primary care for the Total per Capita Cost measure. Hospitalists are increasingly being asked to coordinate and follow-up on post-discharge care as a natural extension of the inpatient discharges they provide. The TCM codes are, and should continue to be, billable by a range of providers, including those who furnish the discharge. As a result, TCM could be performed by providers from the facility or by a patient’s primary care provider – variability that reflects different provider-patient relationships and could skew measure results.

II.E.5.e.3.a.ii. Reliability

CMS proposes to remove specialty comparison from the Medicare Spending Per Beneficiary measure.

SHM opposes the removal of specialty comparison from the MSPB measure. By nature of their practice location, hospitalists tend to see sicker patients, more patients without insurance and/or primary care providers, and a higher proportion of Medicaid patients. We are concerned that removal of specialty comparison will result in skewed results for hospitalists. Given that a Medicare specialty billing code has not existed for hospitalists until this year, we strongly encourage CMS to not finalize this proposal until it can affirmatively show that performance in the MSPB does not need adjustment by specialty.

II.E.5.e.3.b. Episode-based Measures Proposed for the MIPS Resource Use Performance Category

CMS proposed to add 41 new episode based payment measures to the MIPS Resource Use performance category. The measures would be attributed to providers either by billing at least 30 percent of the inpatient E&M visits during the initial trigger event or, for procedural episodes, by billing the trigger code associated with the episode.

SHM broadly supports the move towards episode-based payment measures as they may provide more actionable or useful information to providers and groups. However, we caution CMS that maintaining broad spending measures while implementing episode-based measures effectively double-counts services and potentially penalizes providers twice for costs incurred by the same patients.

SHM notes that nearly half of the proposed episode-based payment measures have not previously been in use anywhere in the Medicare program, including as information in the 2014 supplemental Quality and Resource Use Reports (sQRURs). We recommend finalizing only the measures previously published in the sQRURs and encourage this pathway as a way to introduce new resource use measures.

We also have comments about some measures combining inpatient episodes with outpatient episodes, such as Table 4: Measure 32 Pulmonary Embolism, Acute; Table 4: Measure 33 Upper Respiratory Infection, Acute, Simple; and Table 4: Measure 34 Deep Venous Thrombosis of Extremity, NOS, Acute. Patients with these conditions who are admitted to and managed by the hospital are more likely to be within high-risk populations and/or have significant comorbidities and therefore likely to incur higher costs. The benchmarks developed with outpatient episodes would inherently disadvantage inpatient providers. SHM opposes their use in the MIPS based on concerns about the measure cohort and the exclusion of these measures from the 2014 sQRURs. However, if CMS finalizes these measures for inclusion, SHM recommends divorcing the inpatient and outpatient episodes.

II.E.5.e.3.b.i. Attribution

SHM has questions about the attribution methodology for acute condition episodes (30 percent of inpatient E&M visits during the trigger event). We are concerned that hospitalists – reporting as individuals or as groups – will have a large number of the episode-based resource use measures attributed to them. We ask that CMS provide any data or modeling for how the attribution methodology would function per each measure, as well as expand on which providers would have patients attributed to them. Our concern is that a large number of resource use measures attributed to hospitalists will be confusing and yield too much information to be meaningful to these groups. It would also stymie the purpose of diversifying the resource use measures set if a disproportionate share of measures is attributed to a single subset of providers or groups.II.E.5.e.3.c. Attribution for Individual and Groups

CMS proposes to attribute resource use measures differently based on how providers report in the MIPS. If an EC reports as an individual, the attribution methodology will be applied to the TIN-NPI. If ECs report as a group, the attribution of resource use measures will be at the TIN level. Alternatively, CMS is considering attributing measures to all providers at the TIN-NPI level and aggregating up for groups.

We believe it makes sense to keep the attribution methodology consistent with the way providers choose to report. This would enable individuals and groups to access data in a way that makes sense to their practice. We do not support the alternative group attribution methodology, as groups of hospitalists could have multiple attributions of the same patient-episode. Since hospital medicine uses a shift-based model, patients are handed off from hospitalist to hospitalist (commonly from the same hospitalist group) until discharge. It is conceivable this could result in duplicate attributions within the same group.

II.E.5.e.3.e. Additional System Measures

SHM appreciates that CMS is considering measures from other payment systems for use in the Resource Use category. SHM has consistently been supportive of CMS developing an optional pathway for hospitalists to use performance on other system measures as a proxy for their performance in physician value-based payment programs (PQRS, VBPM, MIPS). We note that with the Medicare Spending Per Beneficiary (MSPB) measure, CMS has some experience with adapting facility metrics for use in provider programs.

As a voluntary option, this could enable greater harmony between the performance agendas of physicians and their facilities and significantly reduce reporting burdens associated with provider-level quality measurement programs.

One of the challenges around adopting additional system measures will be ensuring that attribution is appropriate and relevant to the providers and their groups. CMS needs to consider a methodology that enables proportional attribution that is as close a proxy for a group’s practice as possible. It should be able to identify performance differences between hospitalist groups, or between hospitalists and PCPs, practicing in the same facility. At the same time, many hospitalists practice in multiple locations, making it necessary to identify a methodology to capture performance across settings.

SHM reviewed the available mandatory measures under the Hospital Inpatient Quality Reporting and Hospital Value-based Purchasing programs. We also reviewed measures slated for inclusion into the programs in future years. There are a number of payment or resource use measures that reflect relevant clinical areas for hospitalists and could be adapted for incorporation into the Resource Use category of the MIPS. They include:

- Medicare Spending Per Beneficiary Measure (already in use in VBPM/proposed for MIPS)

- Pneumonia Payment per Episode of Care

- Cellulitis Clinical Episode-based Payment Measure

- Kidney/UTI Clinical Episode-based Payment Measure

- Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage Clinical Episode-based Payment Measure

SHM stands ready to work with CMS to explore and develop a facility-alignment option for hospitalists in the MIPS.

II.E.5.f. Clinical Practice Improvement Activity (CPIA) Category

II.E.5.f.3.a. CPIA Data Submission Criteria: Submission Mechanisms

CMS proposes to allow submission of data for the CPIA category via qualified registry, EHR, QCDR, CMS Web Interface and attestation. In the first year of the MIPS, CMS will require all ECs and groups, or third-party entities submitting on behalf of providers, to designate a yes/no for each item on the inventory.

SHM requests significant clarification on the submission mechanism(s) for the CPIA. Certain activities require the use of a third-party vendor in order to complete the task, whereas other activities, such as those that are associated with systems and process improvement in a hospital, may not require an external entity. Based on the proposed rule, it is unclear how providers will be reporting on activities within the CPIA. It seems that it is CMS’ intent to have the first year of the CPIA category be attestation-based. SHM supports attestation-based CPIA reporting, but notes that this would prevent providers from claiming credit for different activities that are represented by the same description on the CPIA inventory.

SHM strongly recommends CMS identify a pathway for providers to report on multiple projects that may fall under the same item on the CPIA inventory. Many of the available activities are vague and could conceivably encompass two or more distinct quality improvement projects with differing clinical or process improvement objectives. For example, the activity of “Measure and improve quality at the practice and panel level” (Patient Safety and Practice Assessment subcategory) could capture different quality improvement projects such as improving sepsis management and reducing catheter associated urinary tract infections (CAUTI). These discrete projects should each count towards completing an activity for the CPIA category and, under the proposed scoring methodology, give the provider 20 points (10 points for each iteration).

II.E.5.f.3.b. CPIA Data Submission Criteria: Weighted Scoring

CMS proposes a weighted scoring model for activities. Activities that are aligned with CMS national priorities/programs or require performance of multiple actions are weighted as high. All other activities are weighted as medium. CMS encourages commenters to consider patient-centered medical homes as a model for how to evaluate whether an activity should be weighted as high.

SHM is concerned that CMS’ approach to weighting activities favors outpatient primary care practices and may not be representative of the level of commitment and resources necessary for completing a given activity. We strongly recommend that CMS adopt a simpler and more uniform model of scoring activities. This will enable providers and CMS to begin to understand the breadth and depth of activities. It may also mean that multifaceted activities are broken down into “bundles” wherein providers could be scored for individual aspects within the activity per their attestation. If a provider or third party entity reports on the entirety of a bundle, those ECs should receive credit for each of the attendant pieces.

II.E.5.f.3.c. Submission Criteria

CMS proposes to set high-weighted activities at 20 points and medium-weighted activities at 10 points. ECs and groups would need to report on 60 points worth of activities in order to achieve full credit in the CPIA category. MIPS small groups (fewer than 15 clinicians), rural and HPSA clinicians or groups, and non-patient facing clinicians would be required to report on any two activities to receive full credit in the category. MIPS APM participants would receive 50 percent score through their APM participation.

SHM believes there should not be such a wide discrepancy between requirements for small or rural providers and the rest of MIPS ECs and groups. Particularly in the first year, it would be helpful to gather more information about the activities and how much time or resources they require, as a way to better inform future iterations of the program with a more progressive weighting system. CMS could assign a weight of 20 or 15 points to all activities for all groups larger than 15 ECs, parallel to the proposed weighting of 30 points for all activities for smaller groups and individuals. CMS could also ask for voluntary self-reporting of time or intensity required to complete each activity, in order to gain a better understanding of the differences between activities.

We also recommend that CMS consider weighting participation in an APM as either 75 percent or 100 percent of the score for the CPIA category. It is not uncommon for hospitalists to be participating in multiple APMs (such as multiple BPCI bundles). Most APMs require a significant outlay of time and resources, as well as structural process and care delivery redesign, to be successful. CMS has the statutory authority to weight APM participation “at least half of the highest potential score” and should use higher weighting to encourage and reward APM participation.

II.E.5.f.7. CPIA Inventory

CMS created an inventory of more than 90 potential activities for providers to complete in order to receive credit under the CPIA category. SHM believes that, given the breadth of available activities, hospitalists should be able to match the quality and process improvement activities they are already taking part in to items listed in the CPIA inventory.

We note, however, that many of the activities hospitalists participate in are functions either of their hospitals, or of the multidisciplinary teams associated with caring for patients in the inpatient setting. We encourage CMS to ensure that the inventory is wide enough to accept CPIA activities that would enable hospitalists and other providers to get credit for cross-discipline or facility-based quality improvement work.

SHM also believes there will be instances where similar projects could fall under the same item on the CPIA inventory. For example, the activity of “Measure and improve quality at the practice and panel level” (Patient Safety and Practice Assessment subcategory) could capture different quality improvement projects such as improved sepsis management and reduction of catheter associated urinary tract infections (CAUTI). These discrete projects should each count towards completing an activity for the CPIA category and, under the proposed scoring methodology, give the provider 20 points (10 points for each iteration). We recommend that CMS develop a methodology to allow for providers to get credit for doing several projects under the same CPIA that may be focused on different clinical conditions or process improvements.

II.E.5.g. Advancing Care Information Performance Category

II.E.5.g.8.a.i. Hospital-Based MIPS Eligible Clinicians

CMS proposes to assign a weight of zero for the Advancing Care Information (ACI) performance category for hospital-based MIPS ECs. A “hospital-based MIPS EC” would be defined as an EC who furnishes 90 percent or more of his or her covered professional services in sites of service for inpatient hospital or emergency room in the year preceding the performance period.

SHM concurs with the need to have a categorical exemption for providers who are “hospital-based.” However, we have concerns about CMS’ proposed definition of hospital-based. As CMS notes, hospital-based providers actively use hospital-owned EHR systems that are designed for the hospital track of the Electronic Health Record Incentive Program (Meaningful Use). In addition, the clinical and care delivery activities performed by these hospital-based providers are appropriately captured as elements in the facility EHR systems. In many cases, hospitalists, and other hospital-based providers, are actively incentivized to help hospitals meet eligible hospital Meaningful Use requirements.

SHM strongly encourages CMS to reconsider the 90 percent threshold of payments as a mediator for defining a hospital-based MIPS EC. It did not work under Meaningful Use, is not representative of hospital-based practice, and will inadvertently penalize a significant portion of hospitalists. Over the past two years, CMS has issued an automatic exception for hospitalists that incorporates hospital observation services under Place of Service 22—this was a short-term fix to a structural problem within the program. We recommend CMS use this rulemaking cycle to overhaul the definition of hospital-based that moves away from patchwork solutions and allows hospitalists to be confident they will not be unfairly penalized under this category. We believe CMS has the authority to expand the definition of “hospital-based” as MACRA eliminates the penalties associated with the EHR Incentive Program for eligible professionals.

Hospitalist researchers explored the use of thresholds to identify hospitalists and the effect of varying thresholds of hospital E/M codes on the number of hospitalists identified.1 The study, which included observation services in the threshold, identified more than 28,000 physicians at or above a 90 percent threshold. However, nearly 7,000 physicians billed between a 60 and 90 percent threshold. This means at least 7,000 hospitalists who practice predominately in the inpatient setting would be subject to the requirements under the ACI category. These providers face identical barriers in completing any of the tasks or measures under ACI as those above the 90 percent threshold. SHM has heard from members that they are being discouraged from “following” patients post-discharge in efforts to prevent readmissions because such activities could trigger Meaningful Use penalties. This should not be happening; providers should not be penalized for focusing on providing quality patient care and improving care transitions.

SHM offers the following recommendations for the treatment of hospital-based MIPS ECs:

1. Include Observation Services in the Threshold. Observation services are provided in an inpatient setting, despite being categorized as outpatient under Place of Service 22 for the purposes of Medicare billing. Observation care is an integral part of hospital medicine and should be included in any threshold defining hospital-based care.

2. Reduce the Threshold to 60%. A provider who bills 60 percent of his or her services in the hospital should be considered a hospital-based provider, as they are highly unlikely to have an office-based practice, and the majority of their clinical time and billing is associated with a hospital stay. In the Lapps et al study, the bulk of remaining services billed by providers at the 60 percent threshold could be associated with the myriad services provided during, immediately prior to, or following a hospitalization. It is increasingly common for hospitalists to practice in a diverse set of facilities, rotating through rehabilitation or nursing facilities, discharge clinics and preoperative medicine practices. Maintaining a high threshold excludes hospital-based clinicians who are providing and coordinating care during and around hospital stays.

3. If Necessary, Consider Using a Combination of Threshold and Medicare Specialty or Attestation and Threshold. CMS recently approved a Medicare specialty billing code for hospitalists. This identifier could be used to confirm a provider is hospital-based when paired with a less than 90% inpatient threshold. Any provider that is using the hospital medicine billing code and billing primarily within a facility setting (inpatient, post-acute, etc.) would be exempt. Alternatively, CMS could create an attestation system, which could be confirmed using a threshold of billing claims, that would enable more self-determination for the hospital-based exemption.

We note that being classified as “hospital-based” does not exempt providers from using EHR technology. In many cases, “hospital-based” providers are still being held accountable by their hospital to performance on measures and processes under the eligible hospital (EH) Meaningful Use program. We encourage CMS to consider how to recognize this work in assessing performance in this category.

II.E.5.g.8.a.ii. MIPS Eligible Clinicians Facing a Significant Hardship

CMS proposes to adopt a similar policy to Stage 2 Meaningful Use for significant hardships for exceptions to the Advancing Care Information category under the MIPs. The hardships include

insufficient internet connectivity, extreme and uncontrollable circumstances, lack of control over the availability of certified EHR technology, and lack of face-to-face patient interaction. ECs would be required to submit an application demonstrating hardship in one of these categories by the end of data submission for the MIPS performance period (proposed: March 31 the year after the performance year).

SHM supports the continuation of these exceptions as they provide critical relief from reporting on measures and activities that are not feasible for the provider. In recent years, it has been a trend for hospitalists to work in other settings, such as skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) where they do not have control over the implementation of EHR technology. The “lack of control” exception encourages providers to contract with and work in facilities that were not included in the EHR Incentive Programs and may not yet have certified systems in place.

In addition to the “lack of control” exception, CMS has historically granted automatic significant hardship exceptions to the following specialties, which are generally hospital located, but due to the nature of their practice, may not meet “hospital- based” thresholds:

- Diagnostic Radiology (30)

- Nuclear Medicine (36)

- Interventional Radiology (94)

- Anesthesiology (05)

- Pathology (22)

We encourage CMS to continue this practice and include hospital medicine among these specialties. It not only saves time and resources in filing hardship exception applications, but also prevents confusion in determining what providers need to file for a hardship and recognizes that “hospital-based” thresholds are not one size fits all for facility based providers. With the recent approval of a Hospital Medicine Medicare specialty billing code, we strongly recommend that Hospital Medicine be added to this list and included as an automatically excepted specialty.

We also appreciate that CMS appears to have moved away from the five-year limitation to hardship exceptions and discourage CMS from instituting any restrictions on the availability of hardship exceptions. If a provider, such as a hospitalist, can’t control the availability or functionality of a facility-based EHR, they are unlikely to gain such control within a given time period, if ever.

II.E.5.h. APM Scoring Standard for MIPS Eligible Clinicians Participating in MIPS APMs

CMS proposes to reduce the MIPS APM participant reporting burden by eliminating the need for such APM eligible clinicians to submit data for both MIPS and their respective APMs.

SHM fully supports this concept, recognizes that timing for a workable framework in 2019 is tight, and agrees that further development of this concept will be necessary in future years. A fair system for all MIPS APM participants must be established. The overall goals of this system should seek to avoid mismatches between MIPs and APM reporting/goals, and minimize undue provider burden and expense associated with complying under their respective APMs as well as their being held accountable for differing MIPs requirements. We believe CMS needs to make significant adjustments in order to ensure that providers who are participating in good faith in Advanced APMs, but who may not end up meeting QP thresholds, are not de facto required to report on significant sections of the MIPS to protect themselves from penalties.

In the discussion of how the CPIA performance category will contribute to the overall performance score, CMS notes that Congress intended, per § 1848(q)(5)(C)(ii) of the Act, that eligible clinicians who are participating in an APM, as defined by § 1833(z)(3)(C) of the Social Security Act, must earn at least one half of the highest potential score for the category. However, it is unclear, based on the drafting of the proposed rule, whether CMS intends to include eligible clinicians who participate in an APM that meets the statutory definition, such as BCPI, in the MIPS APM scoring, or whether CMS intends to limit the preferable scoring to APMs that meet the requirements for the APM scoring standard. We believe it is clear that Congress intended that the preferable scoring be available to eligible clinicians participating in an APM that meets the statutory definition only, and we request that CMS clarify this in the final rule.

We are also deeply concerned over the use of a “snapshot” of APM participation for the purposes of the MIPS APM scoring. By incorporating only providers participating in the APM on December 31, CMS will be excluding providers who participated in the APM throughout the year. Hospitalist groups frequently have fluid work arrangements, with ECs entering and leaving a practice throughout the year. In addition, this snapshot does not make functional sense with episodic APMs, wherein episodes would be starting and finishing throughout the year.

We encourage CMS to consider and clarify the following scenarios as they finalize policies around APM scoring standards under the MIPS:

1. Providers who are participating in APMs but are hospital-based and excluded from the ACI category would only have a MIPS score in the CPIA category. For example, SHM is currently and will continue to work on getting bundled payments approved as an Advanced APM. For those hospitalist groups who are participating in bundled payments, but do not meet the thresholds for QP, how will they fare under the MIPS?

2. Providers who are not exempt from the ACI category but who do not or are unsure whether they meet the thresholds for QP in Advanced APMs, would essentially be required to meet the reporting criteria in ACI to be safe in the chance they are required to participate in the MIPS. We believe this will be a widespread issue among APM participants as the QP thresholds will be difficult to meet.

3. Under the proposals for the CPIA category, providers who are participating in Advanced APMs but who do not or are unsure whether they will meet the thresholds for QP in Advanced APMs would essentially be required to perform practice improvement activities above the care redesign work of their APM to be safe in the chance they are required to participate in the MIPS. We believe this will also be a widespread issue.

II.E.6. MIPS Composite Performance Score Methodology

II.E.6.a.1.b. Unified Scoring System

CMS proposes six characteristics to be adopted for the MIPS unified scoring system. They include:

1. Converting all measures in the quality and resource use categories into a 10-point scoring system, enabling cross-measure comparisons.

2. CMS would publish measure and activity standards, when feasible, before the performance period begins.

3. There are no “all or nothing requirements;” however failing to report on any measures would yield zero points for that measure, consistent with policies in MACRA.

4. The scoring system would emphasize sufficient reliability and validity, by only measures that meet certain data standards would be scored.

5. Scoring system would incentivize high-priority goals for the Medicare system.

6. Performance at any level would ensure at least some points towards category scores.

SHM supports CMS’ proposed characteristics, particularly that CMS is moving away from “all or nothing” scoring systems. This is a marked departure from policies for the PQRS program. We believe providers should have the opportunity to receive partial credit for good faith efforts in participation and reporting on measures. However, we note that CMS’ proposals for the base score in the Advancing Care Information category appears to be an all or nothing requirement.

II.E.6.a.2.g.i. Calculating the quality performance category score for non-APM Entity, non-CMS Web Interface Reporters

Consistent with our comments to II.E.5.b.3.a.i., SHM is concerned there are not complementary proposals under this section for what occurs when providers report on fewer than the required six measures and do not have additional applicable and available measures to report. CMS’ narrative in the Quality Performance section of the NPRM seems to suggest that providers can report on fewer than six measures without immediate penalty (i.e., a zero on each unreported measure) for unreported measures in the category. SHM requests significant clarification on this language in the proposed rule and recommends that CMS maintain policies that do not penalize providers who cannot report on six measures due to a lack of applicable measures.

II.E.6.a.4.a. Assigning Points to Reported CPIAs

SHM has concerns about the proposal to have activities weighted at medium and high weights, as well as the proposed weighting of certain activities. We believe it is premature to assign differential weights to activities without gathering more information about the resources and time required to undertake an activity. Furthermore, with the emphasis on the patient-centered medical home as the model for assessing activity weighting, CMS’ proposed weightings will disadvantage facility-based providers and specialists.

SHM is concerned that CMS’ approach to weighting activities favors outpatient primary care practices and may not be representative of the level of commitment and resources necessary for completing a given activity. We strongly recommend that CMS adopt a simpler and more uniform model of scoring activities. This will enable providers and CMS to begin to understand the breadth and depth of activities. It may also mean that multifaceted activities are broken down into “bundles” wherein providers could be scored for individual aspects within the activity per their attestation. If a provider or third party entity reports on the entirety of a bundle, those ECs should receive credit for each of the attendant pieces.

II.E.6.b.2.b. Flexibility for Weighting Performance Categories

CMS proposes to assign a weight of zero to categories where ECs may not receive a score in the Quality, Resource Use or Advancing Care Information categories. CMS proposes differential weighting in the quality category if a provider or group reports on fewer than three quality measures.

SHM understands that the weighting will need to be adjusted in order for CMS to assign a composite score on the 1-100 scale required by MACRA. We agree with CMS that differential weighting in the quality category is appropriate for providers who cannot report on more than a few measures. However, we are concerned about the possibility of providers having few quality measures to report and being excluded from another MIPS category. Hospitalists are a class of providers who are unable to participate in the ACI category of the MIPS. Given CMS’ proposals around moving weight from the Resource Use or ACI category to Quality (below, II.E.6.b.2.c.), this would create a difficult situation for CMS to administer and could be a realistic eventuality for some hospitalists. We ask CMS for clarification.

II.E.6.b.2.c. Redistributing Performance Category Weights

CMS proposes to redistribute weight from the Resource Use or Advancing Care Information categories into the Quality category if it has at least three scored measures. If there are fewer than three measures in the Quality category, CMS proposes to redistribute weight from the unscored category equally across the remaining categories.

SHM opposes preferential redistribution to the Quality category as detailed in the proposals. For hospitalists, who are hospital-based and therefore categorically exempt from the Advancing Care Information category, their Quality category would be worth 75 percent of their total composite performance score. While it is true that providers and CMS have the most experience with quality measures, we cannot recommend that three-quarters of a hospitalist’s MIPS score be based on quality metrics that are not fully representative of their practice. As we noted in our comments to II.E.5.b.3.a.i., there are realistically only four measures for hospitalists who report via claims, two of which are narrowly focused on limited clinical conditions.

Consistent with our comments to the MACRA Request for Information, we recommend CMS consider policies with preferential redistribution towards the CPIA category. SHM believes the transferal of weight towards the CPIA Category will encourage quality improvement while reducing administrative burdens and structural disadvantages. It is also the least static category with more opportunities for providers to engage in activities relevant to their practice, and is most closely aligned with and responsive to clinical realities. Providers can more readily analyze data and execute local-level performance improvement efforts than they can engage in the tedious, costly process of developing and shepherding new quality or resource use measures.

II.E.7. MIPS Payment Adjustments

II.E.7.a.i. Payment Adjustment Identifier

CMS proposes to use a single identifier (TIN-NPI) for the MIPS payment adjustment, regardless of whether the ECs reported as individuals or as a group.

SHM believes the use of TIN-NPI as the identifier for the MIPS payment adjustment could simplify how the payment adjustment is applied and create a consistent, clear set of rules for providers under the MIPS. However, we note that there have been significant issues around transparency and accuracy of TINs. Failing to ensure TIN accuracy and completeness, and having complicated and inaccessible processes for rectifying errors, erodes provider trust in the program. As TINs are central to the operation of the MIPS, CMS must rapidly address these concerns.

II.E.7.a.ii. CPS Used in Payment Adjustment Calculation

CMS proposes to assign the composite performance score (CPS) from the performance year to the TIN-NPI in the payment adjustment year. For ECs who change TINs, CMS proposes to use the performance under the TIN(s) from the performance year for their payment adjustment year.

CMS’ proposals would link the payment adjustment with the provider, regardless of whether or not they are practicing in the same TIN as they were in the performance period. SHM acknowledges that this would ensure providers cannot avoid penalties by changing TINs. However, this proposal may make it difficult for some groups to track and anticipate their expected provider payment adjustments. Many hospital medicine groups employ staffing models that have providers joining and leaving TINs with regularity and employ short term or locum tenens physicians to fill gaps. Providers within these groups could have a wildly divergent set of payment adjustments, making it difficult for groups to expect stable and consistent payments. This policy could also create hiring disincentives for both providers and groups, and could create issues for difficult-to-staff areas and facilities. We strongly encourage CMS consider how to mitigate these issues and to remain open to provider feedback in the coming years to address any unforeseen issues with this policy.

II.E.7.c.1. Establishing Performance Threshold

For the performance threshold for the 2019 MIPS payment year, CMS proposes to develop a model based around 2014 and 2015 data (claims, PQRS reporting, QRURs, and Meaningful Use performance). Using this data, they propose to set the performance threshold at a level where approximately 50 percent of providers will fall above and 50 percent below. Beginning in 2021, CMS would use performance data from the MIPS program to determine the performance threshold.

SHM has concerns about the potential for “performance shock” if the first two years of the MIPS use a methodology where about half of providers are above and about half are below the performance threshold. It is conceivable that performance data from 2019 could yield a much less equal distribution, particularly if CMS chooses to move towards a mean for the performance threshold. This could lead to providers receiving a penalty in 2021 after two years of increases, even if their performance did not objectively change. We advise CMS to develop a policy to mitigate instability in payment adjustments as the MIPS transitions to its own data.

II.E.8. Review and Correction of MIPS Composite Performance Score

II.E.8.a.2. Performance Feedback: Mechanisms

Currently, practicing clinicians are often unable to access their Quality and Resource Use Reports (QRURs), rendering any data contained in them ineffective tools for quality and process improvement. Hospitalists report nearly insurmountable barriers in accessing their QRURs in the current CMS Enterprise portal. It is difficult to determine who within a group has the authority to access reports and the log-in process is cumbersome and unnecessarily complicated. In addition, the group member who has authority to access the reports is frequently not a clinician or front-line provider, the intended audience of the reports. SHM believes a significant portion of why groups are not retrieving their QRURs is because of the difficulty involved in accessing the reports.

If the goal is to provide meaningful and actionable information to front-line providers for improving the quality and efficiency of care, CMS should make every effort to streamline the process for retrieving these feedback reports to ensure they are widely and readily available. The reports must also be as transparent as possible, containing specific information about the NPIs associated with the data and clear explanations on how to resolve inconsistencies or errors with provider attribution, patient attribution and calculation of measures.

II.E.8.c. Targeted Review

CMS proposes to create an informal targeted review process to enable providers to address calculation mistakes, data quality issues, or errors made by CMS in their assessment under the MIPS. The EC can submit their request within 60 days of the close of the data submission period. CMS will provide a response with a decision whether a targeted review is warranted. Decisions made based on the targeted review will be considered final.

SHM agrees it is necessary for CMS to have a process for providers to address issues with their MIPS data or payment adjustment. However, we have concerns about the process outlined in the rule.

The timeline for applying for a targeted review does not coincide with the application of payment adjustments. Instead, it is based upon a period of time specified at the end of a performance year submission period. We believe many targeted reviews will be requested in one of two periods: after feedback reports come out or around the beginning of a payment adjustment year. It is unlikely that most providers will identify issues in their data or with CMS calculations immediately following their data submission. We strongly recommend CMS develop a timeline for the targeted review process that address the anticipated needs of providers around the MIPS payment adjustments. This review should be completed prior to the application of payment adjustments.

Hospitalists’ experiences with the informal review processes in PQRS and the physician value-based payment modifier have been marked by frustration and confusion. Decisions seemed to be made without any justification and providers felt they could not understand how or why their requests for review were denied. This lack of transparency made it difficult for providers to address any problems on their end or understand what errors were made by CMS. We urge CMS to adopt a more transparent informal review process that enables providers to have their concerns addressed and to learn from any mistakes in reporting.

II. F. Alternative Payment Models

SHM supports the intent of MACRA in moving Medicare payment to a value-based formula focused on quality, resource use, clinical practice improvement, and meaningful use of certified EHR technology. SHM also supports, what we see as the ultimate goal under MACRA, increased incentive to shift growing numbers of providers into value-based care furnished through alternate payment models (APMs). In implementing MACRA policies, care should be taken to not only structure the MIPS in a way that allows all providers to meaningfully participate, but also to provide a realistic option to move away from fee-for-service to “Advanced APM” participation, which would be to the benefit of both Medicare and participating providers.

While MACRA represents a significant policy change in the Medicare program, many elements of the proposed structure for Advanced APM participation run the risk of negatively impacting progress made to date among providers and existing APMs. We urge CMS to interpret “advanced APMs” in a way that not only supports the maturation of care coordination between physicians and other health care providers already taking shape in existing APMs, but also allows for innovation in the creation of new models. Policies that result in significant distractions or misaligned incentives will hinder the effectiveness of existing APMs by discouraging participation and risks diminishing further innovation.

Definition of APM Entity

As proposed, the current definition of an APM Entity “means an entity that participates in an APM or Other Payer APM through a direct agreement with CMS or a non-Medicare other payer, respectively.” Under this definition, hospitalists participating in APM models that utilize a convener or other third party intermediary (for example in the case of BPCI) would not qualify because they do not generally have a direct participation agreement with CMS. This definition has the potential to be a significant barrier that would automatically disqualify many hospitalist groups from being considered APMs.

SHM suggests an alternative definition for an APM Entity that would clarify meaning and minimize the potential exclusion of APM participating groups: An Advanced APM Entity is defined as an APM entity that participates in an Advanced APM through a direct or indirect agreement with CMS or non-Medicare other payer, respectively.

Determining Physician Participation in APM Entity

In determining which physicians would be classified as part of an Advanced APM Entity, CMS proposes to take a “snap shot” of provider participation as of Dec 31st. We believe that this snapshot should incorporate any providers who participated in the Advanced APM Entity throughout the year, not just at a single point in time. The way the rule is currently proposed, many physicians who actively contributed to an Advanced APM may not receive their incentive benefits if they choose to leave the APM at any point prior to Dec 31st.

We point out again that large hospitalist groups have fluid work arrangements with eligible clinicians entering or leaving a practice at various points throughout the performance period. CMS acknowledges that certain APMs may need to allow for changes in participation, either by adding or dropping participants from the APM Entity, throughout the QP performance period. Therefore, we understand the Rule to require that, in order to be included in the QP determination, the eligible clinician must have participated in the Advanced APM on or before December 31st of the performance year. We request that CMS clarify that the QP determination process does not only consider eligible clinicians that are participating in the APM Entity on December 31st of the performance year.

Further CMS proposes to determine which physicians are part of an Advanced APM Entity through review of an APM participation list or Affiliated Provider list. Given the PECOS attribution issues many of our member provider groups have had with various APM models, this is an important opportunity to ensure similar issues are avoided with Advanced APM attribution. As such, we believe the method by which CMS will collect or compile the Participation Lists needs to be clarified.

The Proposed Rule is not specific as to how these lists will be created. Given that correct physician attribution to the APM will be essential to the QP determination process as well as the APM incentive calculation, we believe it is an important detail to understand. For example, the BPCI program currently relies on the PECOS, which has been very unreliable and has resulted in errors in physician attribution.

We propose that CMS consider alternative methods for obtaining participation lists, such as allowing APM Entities to supply participation lists through an attestation process. The lists could then be audited using part B billing data.

Advanced APMs - Criteria

MACRA requires an Advanced APM to meet three statutorily-defined criteria: (1) Require participants to use certified EHR technology; (2) Base payments on quality measures comparable to those used in the MIPS quality performance category; and (3) Require participants to bear a more than nominal amount of financial risk. Our comments on CMS’s proposed policies on these three criteria are provided below.

A. Certified EHR Technology Requirement

MACRA requires that Advanced APM participants use certified EHR technology (“CEHRT”). CMS proposes that in the first year (proposed to be 2017), an Advanced APM must require at least 50 percent of eligible clinicians who are enrolled in Medicare to use the certified health IT functions to document and communicate clinical care with patients and other health care professionals. This requirement increases to 75 percent in the second performance year.

For these requirements to be achievable by clinicians other than office based practitioners, CMS must reevaluate how “use” of CEHRT by APM providers is determined. Standards for use of CEHRT should take into account the availability and necessity of existing systems in facilities such as post-acute and hospital settings. Neither setting generally possesses physician-level systems that allow for meeting Advancing Care Information requirements, in the post-acute setting in particular, and there are often systems in place that often do not meet ONC certification criteria as laid out for the historical Meaningful Use program. SHM strongly recommends that certified EHR technology for APMs not be tied to Advancing Care Information criteria.

Advanced APM EHR technology should be focused on meeting the needs and goals of the APM rather than meeting predetermined criteria, functionality and simple “use” percentages of APM providers. The traditional concept of “use” of CEHRT must be adjusted to allow for the changing APM landscape and assure the development of specialized health IT modules that support the goals of each APM. The “use” of EHR technology, its requisite functionality, and how the APM plans to meet those needs, should be outlined by individual APMs. CMS can then work with each APM to determine whether or not the expressed criteria will be met.

Furthermore, “use” of any technology within an APM should not imply ownership, control, or the ability of any single user to meet overarching, explicit, criteria – one size does not fit all. For example, according to CMS, over 90% of the nation’s hospitals have achieved Meaningful Use. Hospitalists who are working within facilities are generally super users of their hospital’s CEHRT technology. These hospitalists are most definitely “users” of CEHRT, but are unlikely to be counted in the >50% threshold (or greater in future years) of “use” as currently proposed by CMS. This is likely to be the situation for many providers who are participating in APMs within a larger system or in which the APM entity itself is that larger system. Congress intended to incentivize participation in alternative payment models that will improve care for beneficiaries and remove unnecessary costs from the system. With this fact in mind, they could not have intended to require physician groups to invest in costly and duplicative electronic health record technologies to fully participate. Nor could they have intended to exclude entire specialties or employment models from Advanced APM participation.

CMS recognizes these facts in the NPRM when it states, “APM participants might share common resources, such as the same EHR system and that such sharing will give eligible clinicians flexibility of participation as a MIPS eligible clinician or within an Advanced APM without needing to change or upgrade EHR systems.” It is only logical to extend the “sharing of systems” for cases in which the sharing is between a hospital and clinician. This is a clear opportunity to begin breaking down the false silo between physician and hospital EHRs. To allow for varying employment structures and differing APM needs, APM providers working in a setting possessing certified EHR technology should be deemed to be “using” certified EHR for APM purposes as well. To meet MACRA requirements, CMS could establish a simple attestation process to confirm that providers are in fact utilizing CEHRT, either on their own, or within the facilities in which they are caring for patients.

B. Applicable Quality Measures

MACRA requires the APM to provide payment for covered professional services based on quality measures “comparable to those in the quality performance category under MIPS.” It proposes that an Advanced APM must base payment on quality measures that are evidence-based, reliable, and valid. In addition, at least one such measure must be an outcome measure if an outcome measure appropriate to the Advanced APM is available on the MIPS measure list. Specifically, qualifying quality measures must include at least one of the following types of measures: (1) any measure included on the proposed annual list of MIPS quality measures; (2) quality measures endorsed by a consensus-based entity; (3) quality measures developed under section 1848(s) of the Social Security Act; (4) quality measures submitted in response to the MIPS Call for Quality Measures; or, (5) any other quality measure as determined by CMS.

As described in sections 1848(q)(2)(C)(ii) & (iii) of MACRA, the Secretary may use measures used for a payment system other than for physicians, such as measures for inpatient hospitals, for purposes of the performance categories. The Secretary may also use global measures, such as global outcome measures, and population-based measures. Through the lens of these sections of MACRA, CMS has fairly broad authority to shape the MIPS quality measures category beyond PQRS, and should utilize that authority in the APM framework as well. For example, bundled payment, ACOs, and certainly capitated payments, represent payment systems that could find value in the selection of measures beyond what is currently included in PQRS.

SHM supports the proposal to require APMs to report one outcomes measure and a measure from another set of sources. This seems to provide much needed flexibility for Advanced APMs to select quality measures that best fit the needs of that specific payment/care delivery model. However, measure development specific to the various APM models is still in its infancy. SHM cautions that meeting measure requirements for Advanced APMs should neither be tied to reporting a certain number of metrics beyond the two categories/two measures (1 outcome and 1 from another source) that seem to be specified in this proposal, nor a one-size-fits-all set of metrics.

As such, Advanced APMs should be empowered to determine what measures are most useful based on the goals and design of the APM. In making this determination, the primary questions both the APM and CMS should address are:

1. Does the APM have quality measures?

2. Do those quality measures align with what the APM hopes to achieve?

3. Do the measures help ensure that patients are not being put at risk?

Finally, SHM is fully supportive of the CMS proposal not to tie the Advanced APM participation incentives under MACRA to performance on quality measures. We agree that if the APM is utilizing quality metrics internally to determine gainsharing or other provider incentives, performance on those metrics should not also be tied to incentives such as MACRA’s 5% APM qualified provider bonus.

C. More than Nominal Risk

MACRA requires that Advanced APMs’ participating APM Entities bear risk for monetary losses of more than a nominal amount under the APM, or be a Medical Home Model expanded under section 1115A(c) of the Social Security Act. CMS proposes an Advanced APM must include a degree of down-side risk, meaning that if actual expenditures exceed expected expenditures, CMS can: (1) withhold payment for services to the APM Entity/eligible clinicians; (2) reduce payment rates to the APM Entity/eligible clinicians; or, (3) require the APM Entity to owe payments to CMS. For an APM to meet the “nominal amount standard,” CMS proposes that the marginal risk must be at least 30 percent of losses in excess of expected expenditure, the minimum loss rate, if applicable, must be no greater than 4 percent of expected expenditures, and the total potential risk must be at least 4 percent of expected expenditures. All full capitation risk arrangements meet the Financial Risk Criterion.

SHM is concerned that the proposed definition of “more than nominal risk” does not go far enough to be inclusive of widespread transformation currently taking place through provider participation in existing APMs. We recommend that financial risk be viewed much more broadly than mere percentages of upside or downside risk and formal downside risk should not be the only risk considered. The statute does not require a reading that “more than nominal risk” must mean therefore be “downside risk.” The dictionary definition of “nominal” is “existing in name only” or “very small.” Therefore, “more than nominal risk” does not require downside risk or the specific risk percentages that CMS proposes.

SHM also disagrees with CMS declining to include upfront investment, startup costs, and ongoing costs, which would include technology infrastructure, systems reorganization, dedicated administrative staff, maintenance, and other resource-intensive changes that APM participation requires, as part of the “more than nominal financial risk” calculation. These are costs that could generally be avoided if providers were to forego APM participation altogether and they represent a type of built-in downside risk, as this investment will not be recouped in the event of APM failure.

CMS must develop a methodology to account for startup costs and other investments as part of their analysis of monetary losses under the APM that are in excess of a nominal amount. SHM recognizes that APMs should not be able to include “investment risk” in perpetuity, but APMs should be able to use this as part of their risk calculation for at least a transitional period. These costs could be amortized over the course of a 3 to 5-year transition period and during this time they could be gradually replaced by direct downside risk.

SHM agrees that two-sided risk models are ideal when it comes to alternative payment models. However, for many providers, the reality of shifting to a risk-based approach of delivering care is a task that will take time to achieve. There are clinical considerations for patients, as well as data requirements, that go beyond a simple decision of whether to take on risk, and the care pathways and coordination networks that must be developed to provide high quality care under this framework must be able to evolve with time. As proposed, the definition of “more than nominal risk” excludes most of the current alternative payment arrangements. This effectively penalizes early adopters of current APM models and disincentives providers from continuing or even beginning efforts toward alternative payment arrangements. While SHM agrees that a two-sided risk model is the ideal when it comes to the future of Advanced APMs, CMS policies need to be structured in a way that broadly incentivizes providers to reach that goal rather than only rewarding the very few who have already achieved it.

Qualifying APM Participant (QP) and Partial QP Determination

SHM fully supports and appreciates the proposal to calculate Threshold Scores for eligible clinicians in an Advanced APM Entity under both the payment amount and patient count methods for each QP Performance Period and to use the more advantageous of the Advanced APM Entity’s two scores. This will prevent placing physicians into an untenable scenario that requires them to predict which approach to use. The approach that comes closest to satisfying either threshold, as determined by CMS, is a fair and much less burdensome approach for providers.